Mel King Community Fellowship Program upholds the late civil rights activist’s legacy

On April 3, community advocates from around the U.S. who work in long-term care gathered with members of the MIT community to discuss ways to increase equity in the industry for care workers, families, and the elderly. With its impassioned attendees and emphasis on workers’ well-being, the meeting felt more like a grassroots strategizing session than an academic event. Such meetings have been taking place in one form or another for more than 50 years through the Mel King Community Fellowship Program.

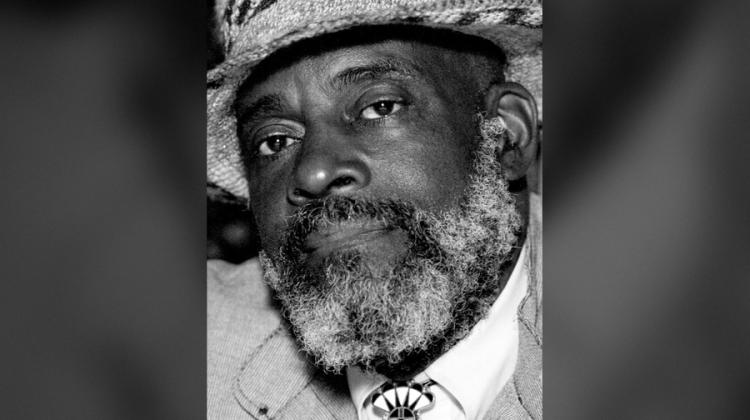

But even as attendees buzzed around the room with an enthusiasm that’s familiar to many involved with the program, this week’s meeting also felt different. That’s because it took place shortly after the passing of its namesake, a local titan of justice and lifelong champion for vulnerable communities, who died on March 28 at the age of 94. Mel King was a longtime political activist and adjunct professor emeritus in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) at MIT — but above all, friends and colleagues remember him as an organizer and an ally.

“Mel was really about coalition building,” says Holly Harriel, a lecturer in DUSP and the executive director of DUSP’s Community Innovators Lab (CoLab), which hosts the Mel King Community Fellows each year. “He wasn’t necessarily discipline-specific or issue-specific. If you were about humanity, personhood, liberation, justice, then Mel was with you and supported you.”

Since King founded the fellowship program in 1970 — a move Harriel says was itself radical at the time — it has supported fellows from around the country who have gone on to spearhead movements in their home communities, some of which grew into national movements. Mel King Fellows have gone on to play prominent roles in the Black Lives Matter movement, the Fight for $15 campaign to raise the federal minimum wage, and the revival of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. Former fellows have gone on to become mayors, lawmakers, and leaders of national labor organizations.

“Having arrived at MIT just recently, I never had the chance to meet Mel King, but he clearly left an indelible mark on the Institute and its people through the Mel King Community Fellowship Program and its emphasis on embracing and serving the needs of marginalized communities,” MIT President Sally Kornbluth says. “As with any great teacher, Mel King left a living legacy in all those he inspired and taught — students, faculty and fellows alike. At MIT, more than 25 years after his official retirement, the light of his loving wisdom and passionate advocacy shines brightly on.”

Monday’s fellowship program event began with a tribute to King. A large photo projected in the background showed him looking inquisitively over the panel discussions all day. Above all, King’s legacy was present in the energetic spirit of the changemakers that gathered.

“Mel was always putting the interests of the community and the interests of the people first,” MIT Associate Professor Phil Thompson says. “Every weekend he’d cook breakfast for anybody who came to his place — I mean anybody. He’d just sit and listen and talk, and he really emphasized service. That’s the spirit that the fellowship program is embedded in.”

Connecting changemakers

Harriel believes the Mel King Community Fellowship Program is the longest-running academic justice program in the country. Founded in 1970 and initially run by Professor Emeritus Frank Jones before King took the helm, the idea was to bring together community activists working on the ground with members of academia to brainstorm solutions to community problems.

“The themes [of the program] always center on community knowledge, community voice, and then principles around justice and multicultural democracy have emerged with different leaders. But the fellowship program is the through-line across it all,” Harriel says. “DUSP and the CoLab don’t operate in a silo. Themes come from the ground up. Our ecosystem does a good job of telling us what’s important.”

As former fellows have gone on to play leading roles in national movements and advocacy organizations, the program’s network has expanded and strengthened. Derrick Johnson, the current national president of the NAACP, for instance, is a former Mel King Community Fellow.

“Mel changed much more than our department and MIT,” DUSP professor and department head Chris Zegras wrote in an email shared with the DUSP community. “It’s plainly clear that the city of Boston, the state of Massachusetts, and beyond, would not be the same without having had the privilege of Mel King as one of its citizens. Massachusetts is often recognized for its leaders — political, literary, educational, technological — among this historical group, Mel King stands at the pinnacle.”

This year’s cohort includes 18 fellows working in the long-term care space in states across the country and in national organizations committed to advancing strategies to create a just and quality long-term care system for caregivers and care seekers alike.

“Mel designed the fellowship program as a way for community leaders and activists to come to MIT and reflect and engage with students and faculty,” Harriel says. “In the beginning, he would bend faculty members’ ears to prioritize the community and invite bidirectional exchange. He was a man ahead of his time because he understood that learning is bidirectional.”

Putting people first

King was South End to the core. The only time in his life he lived outside of the Boston neighborhood was when he attended the historically Black Claflin College (now Claflin University) in South Carolina, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

King’s community work took many forms, from working with at-risk youth and the homeless to organizing demonstrations around issues like affordable housing, job training for the unemployed, and improving public schools.

In 1968, to protest the construction of a parking garage in a site that could have been used for low-income housing, King led a demonstration in which hundreds of protesters camped out in the lot for three days, building tents, wooden shanties, and a large sign welcoming all to “Tent City.” A mixed-income housing complex was later built at the site. The Tent City name has stuck to this day.

King came to MIT as an adjunct professor of urban studies and planning in 1970, the same year he founded what was first the Community Fellows Program and later the Mel King Community Fellows Program. The program initially brought community members from Boston together with DUSP faculty and students to solve problems affecting community well-being.

As the program blossomed, so did King’s involvement in local politics. He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives for nine years, where he was instrumental in, among other things, starting a community gardens program in the state and making Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a state holiday.

But King’s most visible political effort came when he ran for mayor of Boston in 1983. The city was still reeling from violence that erupted following court-ordered desegregation of schools in the mid 1970s, and racial tensions were high. Yet King, who became the first African American to run for mayor in Boston, walked through the streets radiating positivity, says Thompson, who volunteered with the campaign. He recalls that King wore a traditional African dashiki and spoke collegially with supporters and opponents alike. Debates with his opponent focused on idea exchange and the hope each candidate had for their city. His message resonated more than anyone expected, and he finished a surprise second in voting.

King directed the Community Fellows Program at MIT until his retirement in 1996. By then the program had brought in community organizers and leaders from across the U.S. to study and advance financial inclusion, urban well-being, economic development, democratic participation, and more.

Even as King’s political and academic life ended, his commitment to the community continued. After retiring from MIT, he founded and served as director of the South End Technology Center — located back at the Tent City apartments that were down the street from his home. The program still provides computer science training and technology access to low-income individuals.

King worked in other ways to ensure technology was distributed more evenly throughout society. His efforts included pioneering community cable television, expanding underresourced communities’ access to the internet, and more.

He worked with MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms to launch the first fab lab at the South End Technology Center, which subsequently grew into a network of now over 2,500 labs in 125 countries, providing access in a range of underserved communities to the means “to make (almost) anything” according to Professor Neil Gershenfeld, and which inspired a Fab City commitment that Boston, Somerville, and Cambridge have all joined.

“[Last month] we lost a giant who left us with a giant legacy that has shaped our cities, our field, our discourse, and our interactions with each other in a lasting way,” says Hashim Sarkis, the dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning. “Mel King not only imagined what a just city could be, but he made it happen. We gratefully inherit this legacy and we promise to carry it forward.”

A continuing impact

MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning is still known for its focus on community development and social justice. Former MIT chancellor and Professor Emeritus Phil Clay says that’s no coincidence.

“The department has a reputation of being very progressive,” Clay says. “Traditional city planning is pretty conservative; it’s oriented toward downtown and big commercial developments and highway systems. Our department has been much more balanced, with an increasing focus on housing, economic development, and communities. You don’t find as much interest in building skyscrapers downtown. There’s far more talk about public housing and transportation and communities. It’s part of the legend of Mel, and it still fuels the spirit of the department.”

Up until very recently, it wasn’t hard to find King. He’d often be at the South End Technology Center working with children, or speaking with the community fellows, or hosting his legendary breakfasts. He played tennis well into his 80s.

Many remember King as someone who was always there to welcome ideas, ask questions, make connections, and offer advice.

“He understood in a very nuanced way that he had to create a generation of leaders behind him that could carry on his work,” Harriel says. “That’s why you have so many people writing reflections and sharing memories of Mel. He’d plant seeds for a future harvest of change agents and justice seekers and liberation builders. His impact will live on in perpetuity because there are so many of us who he supported.”